I had a brief lesson yesterday evening about what is wrong with administration, public and private, in the UK after unfortunately entangling myself with the Direct Line call centre.

This is no bureaucracy, after all. It isn't the public sector. But unfortunately, in a weak moment some years ago, I seemed to have taken out car insurance with them.

My call was to facilitate what should have been a simple business of extending my car insurance to cover a brief drive in France later this month. It was the culmination of a private sector bureaucracy encounters while undergoing the trauma of trying to buy and sell a house recently, and it really isn't at all impressive.

What strikes me most of all is how unresponsive and inflexible they are. But let's stay with Direct Line.

It took me just over 40 minutes and four different phone calls to talk to anyone human at all - and I don't think, judging by their website, that this transaction can be carried out online.

Still, I happened to have the phone to my ear when the human being answered and the transaction was pretty quick. It was then that I noticed that my card details they keep for me are out of date. Could I change those at the same time? I had after all just paid using the new card for this French trip.

No, because that was a different department. I could be transferred but would have to go to the back of the queue.

I said the life was too short and gave them my phone number, and asked them to call me. No, they couldn't guarantee it.

I tell you what, said the man. I've just checked and the accounts department has no calls waiting. Shall I put you through now?

Clever move this one. Of course I said yes, and went through the usual hideous recorded messages, only to discover - as he must have known - that there was a very good reason why the accounts department had no calls waiting. It was closed.

Now, let's unpack this a little. There is no good reason these days why any consolidated insurance company should not be able to deal with all my transactions in one call. The US insurance giant MetLife has a new app that allows them to see into all their 70 different and incompatible databases and see what each customer needs. Guess how long it took to build? Ninety days.

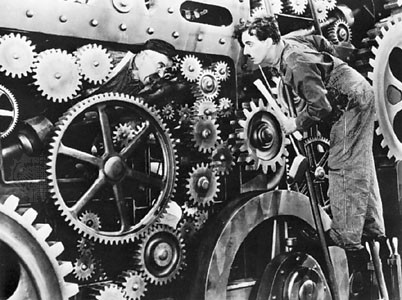

Once again, UK business clings to outdated technology - big IT systems - which make them inflexible and lock in all the inefficiencies.

But there was one other infuriating element of the experience. Like most call centres, we started the ordeal with the obligatory recorded message explaining that they are dealing with unprecedented demand and there is therefore a wait (they were right about the wait, and I paid for it via an 0845 number).

I am an admirer of the system thinker John Seddon, and find myself approaching these issues as I believe he would. Are these periods of high demand not predictable? Why don't they organise their rosters around the patterns of demand, rather than squeeze their customers to fit in with their inflexible rosters?

As it was, the man I spoke to met his target for the time taken to get me off the line, and they were happy. More about these issues in my book The Human Element.

All of which makes me think three things:

1. Once again, why is UK business so timid, so inward looking and so contemptuous of their customers - presumably because they are so often consolidated beyond usefulness?

2. This isn't an issue of public versus private, but even so...

3. How do we prevent Whitehall from believing that this is an efficient model for public services?

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the words blog subscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com.

When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.